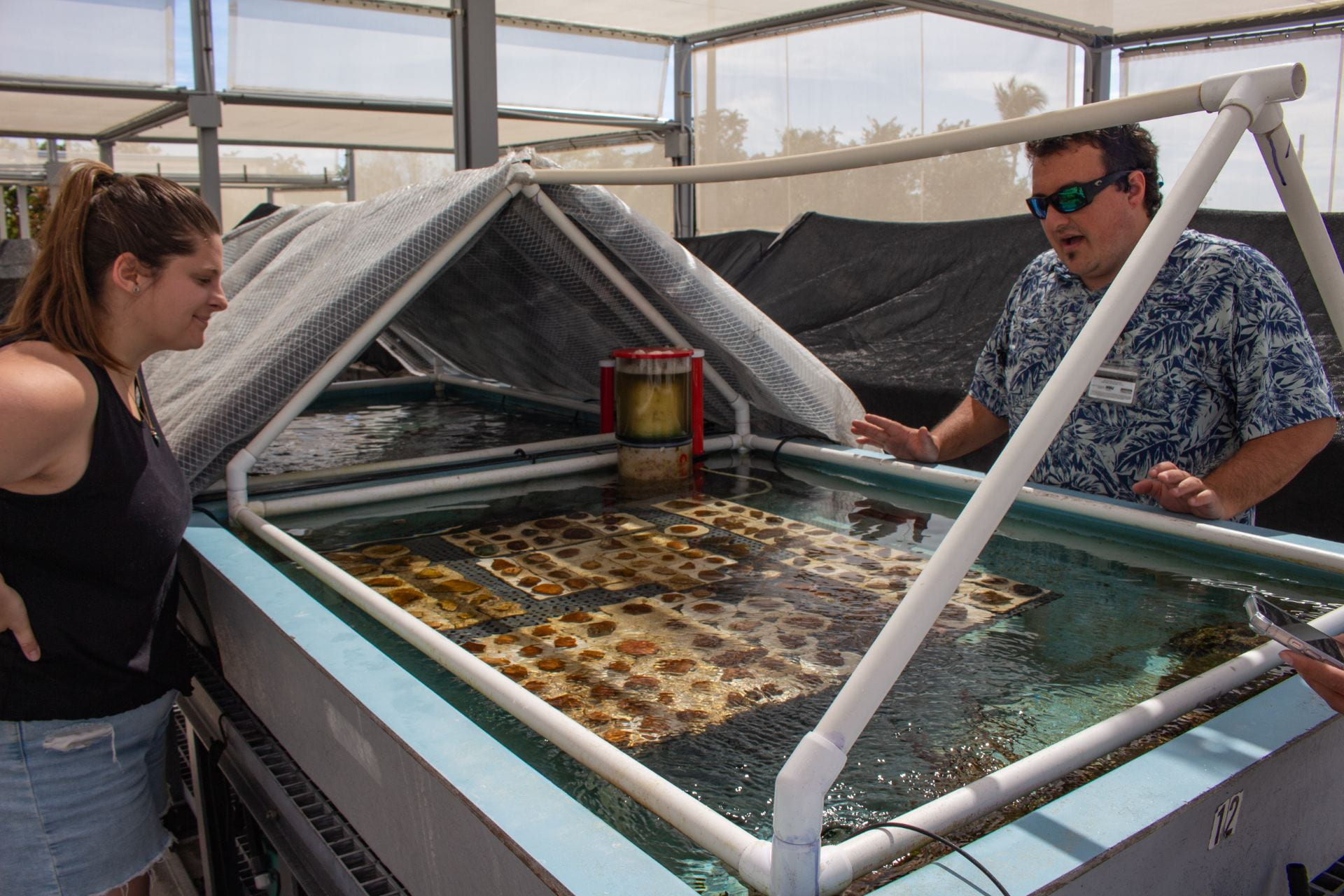

PHOTO BY ALLISON HOLLAND

Chelsea Petrik and Kyle Pisano, on-shore coral reef nursery managers at

the NSU Guy Harvey Oceanographic Center, observe the coral nursery.

Imagine being surrounded by polluted waterways, losing your home, being at risk for disease and not having the guarantee of a future generation. That’s what life entails for a coral reef living in the waters of South Florida.

Chelsea Petrik, one of the on-shore coral reef nursery managers at the NSU Guy Harvey Oceanographic Center, said coral reefs can be affected by shipping through mail, temperature changes, pollutants and light levels, but especially by bacteria and disease.

“This area of the world is unlike anywhere else. In South Florida, the primary reason [for coral degradation] is coral disease. It affects the massive, bouldering corals,” she said. “We find more disease in warmer temperatures since bacteria have more of a chance to spread. There’s a team here that works on [disease] intervention. It totally works in some species, but it’s not a one treatment fits-all. It’s not easy to fix a whole reef area, you need different techniques to treat different corals.”

The NSU Guy Harvey Oceanographic Center has overseen an on-shore and off-shore coral nursery since 2012. The on-shore nursery contains around 60 tanks.

Petrik said the nurseries care for, treat and aid corals through either asexual or sexual reproduction. This includes maintaining their water quality, simulating lunar/solar cycles and providing substrate for corals with the hope that they will eventually be out planted back into the natural reef system.

“[The] majority of our year is just taking care of tanks and corals. When they release progeny, we collect it and conduct assisted fertilization,” she said. “They use moonlight and temperature as a cue to actually release their gametes, [and] we simulate these conditions. Once the larvae are ready, that’s when they look for a substrate. We provide substrates, like tiles, that have biofilm, different colors and a texture similar to a reef. We will settle the corals and then transfer them to the off-shore reef, or directly outplant them.”

Petrik, who focuses mainly on the sexual reproduction of corals, hopes that by studying the entire lifespan, more can be learned about coral genetics and immunity to certain diseases.

“Us as scientists are looking for certain genotypes that are more or less susceptible to coral bleaching,” she said. “We want to use their offspring for reef restoration. A robust brood stock that has traits in them that makes them resistant to heat, and pollution. [Also], how they respond to light, acidification, disease, and water quality affects the choices of which corals go into the nursery.”

Corals can also reproduce asexually, by growing new coral from a piece of existing coral, known as fragmentation.

Abigail Renegar, research scientist in the Department of Marine and Environmental Sciences, presides over half of the on-shore coral nursery and focuses mainly on the asexual reproduction of corals.

“We have coral polyps in the laboratory, and design systems that enable them to have coral spawning year-round, at multiple times per year, and we use those new coral babies to restore the reef. [It’s] on-shore reproduction of corals for reef restoration,” she said.

So far, the GHOC coral nursery has been instrumental in distributing healthy corals back to natural reefs.

Kyle Pisano, another on-shore coral reef nursery manager who focuses on the asexual reproduction of corals, worked on coral reef restoration after receiving corals from the Marquesas Keys, a group of islands off the coast of Key West.

“In 2019, we received a lot of corals from the Marquesas, ahead of the disease wave. We also picked endemic corals that had survived the disease,” he said. “The mortality rate was so high, we were worried that we were going to lose all the genetic diversity in South Florida.”

After being housed in the nursery, Pisano said the corals could have been distributed pretty much all around the world.

Petrik said students looking to get involved in coral reef preservation have a lot of opportunities.

“The citizen’s aspect of science is growing. It was very technical, but now it’s more inclusive. If you’re an avid scuba diver, [and] if you see signs of bleaching, you can submit that data and it gets compiled,” she said. “NSU students [can] come out and volunteer, they can start learning research or aquarium skills. Whether [that means] being an extra diver or collecting samples, getting engaged with the restoration practitioners can be a huge help.”

Be the first to comment on "NSU coral nurseries work toward reef restoration"